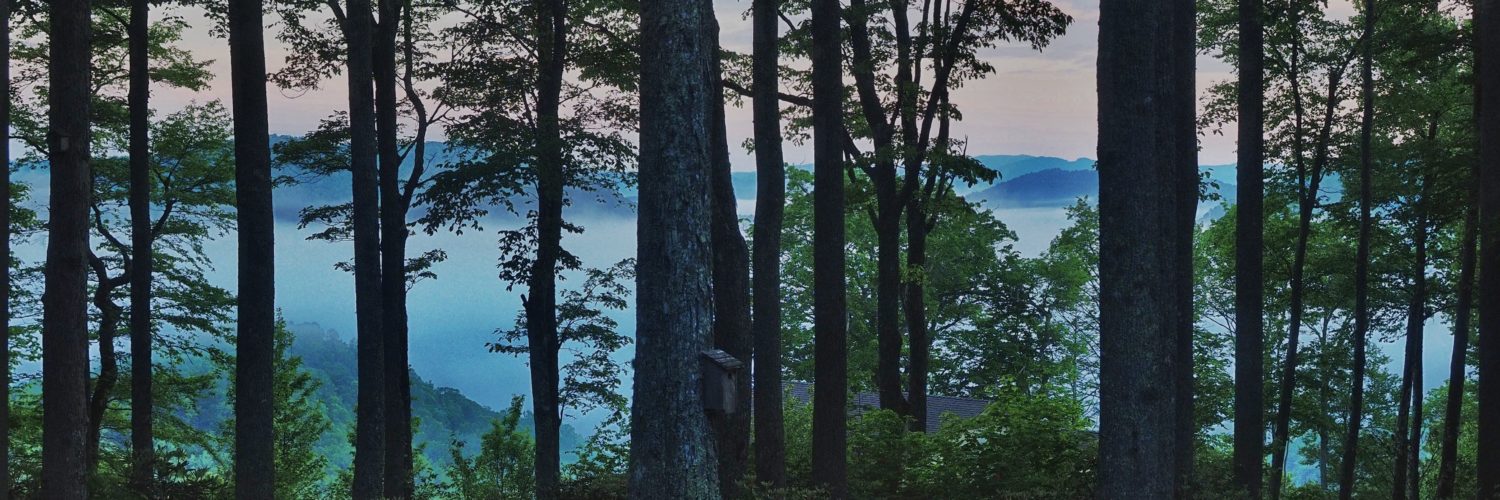

Photos from the pond at Montreat:

Tag: Appalachia

Backyard saplings and the Appalachian ecoregion

As a kid one of my favorite pastimes was romping through the woods that ringed the neighborhoods I lived in, areas that had been carved out of forests and fields as cities spread into the countryside. These trees were a constant source of fun and frolic, woods and creeks that I loved to hang out in. This simple, generic idiom best describes my relationship with the woods – I just like to “hang out” in them. This has remained true all my life.

Now, as an adult, I live on a wooded Appalachian hillside in a neighborhood surrounded by trees. When our subdivision was built in the 1990s the developers gave it a sylvan-themed name (“Woodland Hills”) and tagged the streets with nature-evoking titles like “Wilderness Road” and “Wildflower Drive.” Despite their efforts with wordplay, the term “wilderness” seems a bit out-of-place with the asphalt roads, power lines, and houses that make up our neighborhood. I suspect that this irony was lost on the developers.

Naming ironies aside, this is where I live. And while suburban, our yard, like such lots in the mountains, is chopped out of a hill. A flat spot was sliced from the slope, a drainage system was dug around the foundation, and a retaining wall of railroad ties was placed in the backyard. Collectively these were designed to channel water away from the house and to keep the carved hillside from following its natural inclination to erode downhill. Above the retaining wall is a mess of ground cover intended to deter erosion and mask the gash left by excavation.

Above that are the woods, which were (relatively) untouched by the developers. Our yard includes oaks, maples, tulip poplars, hickories, and pines, some 50 to 60 feet tall. Our lot is intersected by a chain link fence and a few small paths for easy human and canine passage. Above our property is another road with more houses and more woods running up to the top of the ridge. You could walk through the woods to the top of our mountain and follow the wooded ridges east all the way to the Blue Ridge Parkway, crossing several roads that traverse the ridges along the way. There aren’t trails from here to the Parkway, and much is private property, but it could be done.

Geographically, we live on the north-facing slope at the mouth of Reems Creek Valley. Reems Creek flows down from the western slope of the Blue Ridge, past our neighborhood, and on to the French Broad River. Our hill and this valley are part of the larger Appalachian – Blue Ridge forest ecoregion, which according to the World Wildlife Fund, “represents one of the world’s richest temperate broadleaf forests.” This area was heavily timbered early in the 20th century, and while I have no records of logging on what is now our property, there’s plenty of evidence that these trees are second or possibly third growth. Adding to the mystery is an old roadbed in the corner of our lot that could have been a logging road at one time.

This is very much suburbia – the sounds of peepers in the evening are tempered by the mechanical groan of the neighbor’s air conditioner, while the calls of the morning birds on the hillside are mixed with highway sounds from I-26 a mile or so away. On a winter’s day you can look across the valley and see Hamburg Mountain in Weaverville with its garish cover of houses. There are several light industrial plants within a few miles of our house. All this suburbia notwithstanding, the woods that fill the hills and valleys around here are part of a vibrant, verdant ecoregion, a small portion of the larger canopy that covers this part of the Appalachian mountains.

I’ve been thinking about this verdancy during an ongoing foray into my backyard, a place where it’s easy to understand how a forest can grow and spread. It’s a fertile place, where every year an astounding number of saplings spring forth, youthful sprouts that emerge from seeds scattered from the taller canopy above. Our upper yard is relatively undisturbed forest floor, forming the perfect breeding ground for young trees. Maples, pines, oaks, and tulip poplars seem to be the most fruitful – saplings from all these trees dominate my yard, bounding from too-small-to-notice to 6-8” tall in a very short time, especially given the rainy summer we’re having this year.

Countless saplings had taken root in the embankment above our retaining wall, seeking this break in the canopy to do that whole acorn-to-mighty-oak thing. On our north-facing lot direct sunlight is at a premium, so in order to keep the canopy clear some sapling weeding was in order. The embankment is too steep to stand on so I placed a ladder on the hillside ground cover, systematically moving it along the retaining wall so I could remove saplings. All the recent rain made it easy to pull out these small trees with their roots intact. Over the course of several hours I pulled over 100 saplings from the embankment – a fledgling forest in and of itself. I felt a bit guilty thinning these baby trees, but for every one I pulled I spotted another couple starting to grow.

As I was removing these saplings, I found myself reflecting on the lushness and fecundity of these little trees. Tulip poplars alone are remarkably fertile. A study in 1966 found that a one-acre Appalachian stand of tulip poplars produced 1.5 million seeds per acre. One person reported that they planted a 5′ tall tulip poplar in their yard and it grew to 20′ tall in 36 months.

Based on how quickly and thickly tall trees sow their young in my yard, I could see how, unchecked over time, trees will return the area to its native forest. There are hints of this process here and there. In the country you’ll see old barns and outbuildings with trees growing through the windows and roofs, establishing a forested foothold. It even happens in town – there’s a shell of a building in Asheville’s River Arts District with a healthy little glade emerging through its shattered roof. It seems that trees have a long range development plan of their own, willing to slowly dominate, one sapling at a time, as generations of humans march past.

In my tiny section of the Appalachian forest, I marvel at the heartiness of these saplings, ambitious versions of their relatives that tower above. I’m constantly surprising myself that I can pull an entire tree out of the ground and toss it on a pile of similarly sized trees. I smile at the notion that this act gives me the power to keep the forest at bay. It’s a pleasant folly that I like to entertain.